The gravel road from the "highway" to Monteverde is so bad that it has become

legendary.

The gravel road from the "highway" to Monteverde is so bad that it has become

legendary.Home : Travel : Costa Rica : One Part

Upon landing in San Jose, we were met by Miguel and Miguel, driver and tour

guide

for our trip up to Monteverde.

Upon landing in San Jose, we were met by Miguel and Miguel, driver and tour

guide

for our trip up to Monteverde."How long have those shanty towns been there?" I pointed and asked Miguel the guide.

"We never had those before. Those are about two years old," he responded, "they are squatters waiting for the government to do something."

What caused the sudden rise of the shanty towns?

"Poverty."

With a touch of heat stroke and the vibrations of the Cessna still in my bones, I was in no mood for two hours on the windy Interamerican highway. I recalled Jeffrey's words.

"Look at the map. The highway goes straight over the mountains. It's crazy. The only reason they built it that way is because it goes by an ex-president's farmland."

Diesel fumes, traffic, potholes, and curves make any kind of ground travel in Costa Rica trying. The Miguels made the time go pretty fast by spotting wildlife, explaining the history of local towns, and talking about Costa Rica in general. It pained me to think that these two guys had to turn right back around in Monteverde and take some tourists back to San Jose. After two hours, we had reached the Pacific coastal flats near Puntarenas.

The gravel road from the "highway" to Monteverde is so bad that it has become

legendary.

The gravel road from the "highway" to Monteverde is so bad that it has become

legendary.

"The people in Monteverde don't want it paved because that will bring in mass tourism," Miguel explained. "They had 2500 people here ten years ago and last year 60,000. There were three hotels; now there are 20."

The road surface, at least for the first 15 miles or so, wasn't that bad and the views of the rolling hills, Gulf of Nicoya, and Nicoya Peninsula were spectacular. We passed through mile after mile of brown dry hillsides being used seasonally for grazing cattle.

"All of this land was primary rainforest when the Quakers moved here in 1951," Miguel said. "There were 44 of them who came down from Alabama in 1950 to escape being drafted in the Korean War. We got rid of our army on December 1, 1948, and that's why they came down here. They drove down in trucks through Mexico and arrived in 1950, then they looked around Costa Rica for a year before settling on this area because it was good for dairy farming, which is what they knew how to do. They started a cheese factory because that would get to market in good condition even when this road was very muddy and difficult. This is still the part of Costa Rica that produces the best cheese."

What about the cloud forest?

"The Quakers bought the cloud forest to protect the watershed for their dairy

farm," Miguel pulled out a postcard of the brilliant golden toad, "When

scientists discovered this frog, there was a big effort to add to this cloud

forest and the Quakers donated the land to a science reserve. Now it is about

10,000 hectares [25,000 acres]. This postcard is about the only place that you

are going to see the golden toad, by the way, because nobody has seen one for

many years in the wild. Amphibians are becoming extinct all over the world and

nobody knows why."

"The Quakers bought the cloud forest to protect the watershed for their dairy

farm," Miguel pulled out a postcard of the brilliant golden toad, "When

scientists discovered this frog, there was a big effort to add to this cloud

forest and the Quakers donated the land to a science reserve. Now it is about

10,000 hectares [25,000 acres]. This postcard is about the only place that you

are going to see the golden toad, by the way, because nobody has seen one for

many years in the wild. Amphibians are becoming extinct all over the world and

nobody knows why."

The last ten miles were pretty rocky, but after 90 minutes on the gravel road, we sat down to lunch at the plush Monteverde Lodge. After the communal tables at Tortuguero and Corcovado, it was disappointing to be stuck at our own table and not get to meet anyone. On the plus side, the lodge has a sparkling 15-person Jacuzzi in a plant-filled greenhouse. That's where we spent the afternoon, too tired to do anything else.

[The lodge is interesting because it was financed by US AID funds. I talked to

Michael Kaye about it.

[The lodge is interesting because it was financed by US AID funds. I talked to

Michael Kaye about it.

"They ran out of money so they started financing projects in Costa Rica with loan guarantees. Nobody paid them back except me and I only paid them back because I didn't know that I wasn't supposed to. They were so happy that they've inaugurated this hotel five times. A friend of mine called me up the second time and said he'd heard that a new AID-financed hotel was going up in Monteverde. He thought I'd be upset that AID was financing my competition, but it turned out that they were just inaugurating Monteverde Lodge again."]

For general orientation, you might want to Check the overall map of Costa Rica again (80K).

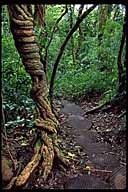

Along with Ken and Flo, a vet from Seattle whose specialty is rescuing

wildlife injured by oil spills, we toured the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve

as a pack of 13 tourists and one guide. We dutifully followed our guide along

the trail, which was made of tree-section "cookies" covered in chicken wire.

Every now and then the group would stop and we'd ask the people in front `Why?'

The highlight of the trip were some glimpses at Quetzals, a bird almost always

preceded by the adjective "resplendent." The name comes from an Aztec word

meaning "precious" or "beautiful," and the birds, even viewed from a great

distance, live up to their billing. They are mostly iridescent green in color.

The male has just enough bright red belly to form a perfect art school color

balance with the green body. The male also has two tail plumes longer than his

body, which make him look a trifle ungainly.

Along with Ken and Flo, a vet from Seattle whose specialty is rescuing

wildlife injured by oil spills, we toured the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve

as a pack of 13 tourists and one guide. We dutifully followed our guide along

the trail, which was made of tree-section "cookies" covered in chicken wire.

Every now and then the group would stop and we'd ask the people in front `Why?'

The highlight of the trip were some glimpses at Quetzals, a bird almost always

preceded by the adjective "resplendent." The name comes from an Aztec word

meaning "precious" or "beautiful," and the birds, even viewed from a great

distance, live up to their billing. They are mostly iridescent green in color.

The male has just enough bright red belly to form a perfect art school color

balance with the green body. The male also has two tail plumes longer than his

body, which make him look a trifle ungainly.

"The Quetzal is the national bird of Guatemala," Amuel, our guide explained, "but you can't find any there because they've deforested the whole country. The only place to see Quetzals is in Costa Rica. They come here to Monteverde to nest, usually February or March through June because that's when the wild avocado tree that they like bears fruit. If you were here in February, you'd be able to see 15 birds from this spot."

I tried to fall in love with the Quetzal but couldn't. Maybe it was the persistent rain and high winds. Maybe it was the mob of tourists we were stuck in. However, I think it is most likely the fact that Quetzals are stupid. They don't mate for life. They don't form communities. Comparing them to Scarlet Macaws is like comparing a California bleached blonde to David Hume. [Informed sources tell me that the preferred term for bleached blonde these days is peroxide-dependent.]

All of the post-Quetzal wildlife was anticlimactic, but our Amuel did display a remarkable knowledge of and affinity for poisonous plants.

"A lot of the Ticos who come here have problems," Amuel said. "They leave a lot of Coke bottles in the forest and they touch everything. Many of the plants are toxic so they go home with problems."

We were happy to get back to the slide show at the park entrance. The slide show was fantastic. The photographers are local residents Michael and Patricia Fogden, persuasive exponents of the "f8 and be there" school of photography. They've got sequences of snakes eating frogs, frogs eating frogs, snakes eating snakes, snakes pretending to be flowers and trying to eat hummingbirds, golden toads mating, Quetzals nesting, and various mammals.

Note the disgruntled hummingbird in the background.

Note the disgruntled hummingbird in the background.

After lunching with Ken and Flo, we walked through downtown Monteverde and

Santa Elena, the adjacent Tico town. There sure wasn't much to do here for the

locals. A couple of "supermarkets," a clinic/pharmacy with one doctor ("you

often have to wait two hours," Oscar said later), a soccer field (in use, as

were all the fields we'd seen in Costa Rica), a small Catholic church, and a

bank. The basic mode of transportation seemed to be carrying heavy loads on

foot back to tin-roofed shacks, yet this is allegedly one of the more

prosperous rural towns in Costa Rica. Some of the older folks ride horses, but

young people prefer motorbikes.

After lunching with Ken and Flo, we walked through downtown Monteverde and

Santa Elena, the adjacent Tico town. There sure wasn't much to do here for the

locals. A couple of "supermarkets," a clinic/pharmacy with one doctor ("you

often have to wait two hours," Oscar said later), a soccer field (in use, as

were all the fields we'd seen in Costa Rica), a small Catholic church, and a

bank. The basic mode of transportation seemed to be carrying heavy loads on

foot back to tin-roofed shacks, yet this is allegedly one of the more

prosperous rural towns in Costa Rica. Some of the older folks ride horses, but

young people prefer motorbikes.Practically everyone we'd met in Tortuguero was staying at the Monteverde Lodge as well. We ran into Chris and Jill and they drove us over to El Sapo Dorado ("The Golden Toad") for dinner. All the guidebooks say this is the finest restaurant in Monteverde and it is certainly the most expensive. The descriptions of the dishes and the tiny portions matched those of gourmet restaurants in the States, but all four of us thought the food at the Monteverde Lodge was far better.

It was at most 1 km from the restaurant back to the lodge, but the road was so bad that it felt like a real odyssey. Oscar Fennell was working the desk and we asked him about the paved road controversy.

"It's about half and half. If somebody gets sick and has to go to the hospital, it costs 8000 colones [$50] for a taxi because the road is so bad. For a family where only the father is working, that's about week's income."

"Everyone here with some money has built a hotel in the last few years. They expected a bigger market than actually developed. They think that if the road is paved, people will come here for the day and not stay in Monteverde. I personally don't agree with this."

What about just plain Tico folks who live in Santa Elena?

"A lot of farmers who live up here don't care about tourism. They want the road paved because they have vehicles to maintain and can't afford to keep buying tires and suspension parts. What's happening right now is that the community has agreed to pave the roads up here between Monteverde and Santa Elena and the Reserve, but the government is still holding off on paving the road up here from the highway."

We went to the Quaker meeting at 10:30. About 100 people eventually

filed into the rectangular room with benches arranged in concentric rings

around the center. People sat in silence, mostly with their eyes open but not

staring at anyone in particular or roaming about the room. After 35 minutes, a

white-haired gentleman named Francis stood up.

We went to the Quaker meeting at 10:30. About 100 people eventually

filed into the rectangular room with benches arranged in concentric rings

around the center. People sat in silence, mostly with their eyes open but not

staring at anyone in particular or roaming about the room. After 35 minutes, a

white-haired gentleman named Francis stood up.

"I have a story to tell that a lot of the older folks here have already heard, but I think it is worth retelling anyway. It was some years ago in West Pakistan, where we were trying to help some people. It is a very different place from this but in some ways similar. This was on the edge of a desert.

"One day I was walking through the woods and came to a clearing. I found there a camel in the middle of the clearing and by the edge a person in distress. It was a girl who had apparently been put in charge of this camel by her parents and had somehow let go of the rope. We spoke different languages, but I came to understand that she'd tried many times to recapture the camel and that it always managed to back away from her.

"By signs and gestures, we developed a plan. I would attract the camel's attention and she would come up from behind it and grab the rope.

"I walked up in front of the camel and talked to it and sure enough, the plan worked. The lesson I got out of this story is that you never know when you may get an opportunity to help people. You might just be taking a walk in the woods and come upon another person in need. You probably won't find anyone with a camel around Monteverde, of course."

Francis sat down and a woman stood up and repeated the story in Spanish for the benefit of kindergartners from the adjacent school. Then the meeting continued in silence for another 10 minutes.

"Does anyone have any afterthoughts?" a bearded 30-year-old asked.

I stood up and introduced myself.

"Francis's story reminds me of when I was in Cairo, Egypt. I was traveling with my friend Bruce and it was our first morning in the city. We passed an old man and a young boy trying to lift a very heavy tree stump up onto a donkey cart. This stump weighed at least 400 lbs or 200 kilograms. Four or five taxi drivers were parked a block away, but none of them got out to help the man and boy. Bruce and I stopped and tried to get the stump on the wagon, but couldn't. It was just a little too heavy. However, the fact that we had stopped spurred one of the taxi drivers to get out of his car and come over. Together, we were able to get the stump on the wagon and the old man and boy went on their way. The lesson I learned from this is that it only takes one person helping to encourage others to help as well."

My story was translated into Spanish, there were a couple of announcements in English, then the meeting was declared over and everyone hugged or shook hands with big smiles. I sat down next to Lucky Guindon who was one of the original 41 settlers.

"I was 18 when I came down here from Iowa. My husband Wolf had been imprisoned

for refusing to register for the peacetime draft. The U.S. had always been

critical of Germany for having a peacetime draft and then as soon as the war

was over, it picked up the practice itself.

"I was 18 when I came down here from Iowa. My husband Wolf had been imprisoned

for refusing to register for the peacetime draft. The U.S. had always been

critical of Germany for having a peacetime draft and then as soon as the war

was over, it picked up the practice itself.

"We came to Costa Rica because it had just abolished its army and people talked about it as a peaceful place. `More teachers than soldiers,' was the slogan back then, although there are a whole lot more civil guards than there were. I guess there is a lot more crime too."

How did people feel about the U.S. now that it had abolished its draft?

"None of us really had an animosity toward the U.S. Most of us are still U.S. citizens, for example, and a lot of people went back and forth."

What about the paved road controversy?

"Nobody besides some businesses wants a paved road. It is just too dangerous. I asked a tour bus driver what he thought once and he gave exactly the same reasons that I would give: (1) people will drive too fast if the road is paved, (2) too many pedestrians walk in the road, and (3) hordes of people would come up for day tours."

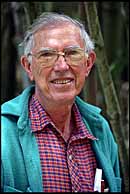

I got more of the original story from Marvin Rockwell, who is tall and thin

with the genial manners you'd expect from a 73-year-old southerner.

I got more of the original story from Marvin Rockwell, who is tall and thin

with the genial manners you'd expect from a 73-year-old southerner.

"We left Fairhope [Alabama] on November 4, 1950 and arrived in San Jose on February 4, 1951. We had one truck and one jeep. I drove the truck."

Was that how long it took to drive straight through?

"We weren't trying to set any speed records, but we didn't stop to sightsee or anything. Our first delay was at the U.S./Mexico border. U.S. Customs wanted an export license for the jeep. We had to wire to Washington to get it and it took eight days."

Had he been imprisoned?

"Oh, yes. I was in a federal prison in Tallahassee, Florida for four months. I was sentenced to one year and a day, but was eligible for parole after four months."

What kinds of criminals were in there back then?

"Oh, car thieves, tax evaders, bootleggers and a few narcotics offenders."

How did the Costa Rican government take to a foreign religious community and did he think it would be different today?

"We were welcomed. Of course, Costa Rica was much smaller back then. The

total population was only 800,000 in 1950. It is more difficult now to get

residency and citizenship because they've had so much immigration from violent

countries like El Salvador and Nicaragua."

"We were welcomed. Of course, Costa Rica was much smaller back then. The

total population was only 800,000 in 1950. It is more difficult now to get

residency and citizenship because they've had so much immigration from violent

countries like El Salvador and Nicaragua."

How did he feel about the U.S. now?

"Oh, I've been back many times. I even went back to a town just outside of Indianapolis for six years so that my children would learn English as native North Americans. I've got four kids and three of them are living in the Los Angeles area. They couldn't resist the bright lights. My daughter lives in Santa Elena, though."

What were the sons doing up in LA? Farming? Were they able to maintain their Quaker faith in a godless place like LA?

"No. One of them belongs to a meeting in Whittier, but the other two don't. None of them are farming. My 34-year-old son has a degree in engineering but he's working in room service at a Marriot Hotel in Anaheim."

Just how tough was it to make a living as a dairy farmer here?

"Not very. If you have 10 cows, that is enough to be comfortable. Just as in the U.S., the government sets a minimum price to be paid for milk."

Thursday, January 26, 1995

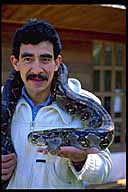

Having seen the Butterfly Farm the day before, we spent the morning

looking at beautiful, poisonous, or simply eerie reptiles in the Serpentarium.

Fernando, the proprietor, didn't speak any English, but he was only too happy

to help a struggling photographer.

Having seen the Butterfly Farm the day before, we spent the morning

looking at beautiful, poisonous, or simply eerie reptiles in the Serpentarium.

Fernando, the proprietor, didn't speak any English, but he was only too happy

to help a struggling photographer.

We then returned to the Monteverde Cloud

Forest to hike to the Continental Divide. Without a guide, we didn't spot much

wildlife, but the hike was infinitely nicer than two days before. It was a

sunny day, which lightened our mood, but contrasty sunshine and high winds made

photography almost impossible. [I learned later than Monteverde is typically

very windy from December through March.]

We then returned to the Monteverde Cloud

Forest to hike to the Continental Divide. Without a guide, we didn't spot much

wildlife, but the hike was infinitely nicer than two days before. It was a

sunny day, which lightened our mood, but contrasty sunshine and high winds made

photography almost impossible. [I learned later than Monteverde is typically

very windy from December through March.]

Once up on the Continental Divide, we could see all the way down to the Gulf of

Nicoya, part of the Pacific, and almost to the Caribbean.

We lingered so long

in the Reserve that we didn't get out until 4:30, by which time the only

telephone for several km had been locked up. We weren't going to be calling a

cab as planned. Just as we were trudging out of the reserve, a subcompact

Suzuki Swift creaked by over the rocky road. Paul, a Canadian who'd driven

down here from Ontario, gave us a lift.

We lingered so long

in the Reserve that we didn't get out until 4:30, by which time the only

telephone for several km had been locked up. We weren't going to be calling a

cab as planned. Just as we were trudging out of the reserve, a subcompact

Suzuki Swift creaked by over the rocky road. Paul, a Canadian who'd driven

down here from Ontario, gave us a lift.

"I didn't leave Colorado until December 10th. The road down here isn't that bad. I had to pay a total of $200 in bribes at various customs stations and those were the only bad experiences I had."

What about people breaking into his car?

"The State Department is full of old ladies who think that you're going to be

mugged, raped, and killed the minute you step across the border. The fact of

the matter is that all of these Central American cities are safer than U.S.

cities. These people should be worrying about Philadelphia and Chicago and

Buffalo, New York which is where I grew up. I parked my car in well-lighted

places, usually in front of the hotel where I was staying and I didn't have any

trouble."

"The State Department is full of old ladies who think that you're going to be

mugged, raped, and killed the minute you step across the border. The fact of

the matter is that all of these Central American cities are safer than U.S.

cities. These people should be worrying about Philadelphia and Chicago and

Buffalo, New York which is where I grew up. I parked my car in well-lighted

places, usually in front of the hotel where I was staying and I didn't have any

trouble."

"If you're a native, you probably have something to worry about. If you're a gringo, you're OK."

With three people in the car plus all my cameras and Paul's camping gear, the oil pan scraped on some of the rocks. Paul didn't seem to notice.

"What you really need are some good guidebooks from people who've done it. The

Harvard guidebook is OK, but the Berkeley guide is even better. AAA knows

nothing about Mexico. The Mexicans have been doing a lot of work on their

roads in the last five years but AAA hasn't noticed."

"What you really need are some good guidebooks from people who've done it. The

Harvard guidebook is OK, but the Berkeley guide is even better. AAA knows

nothing about Mexico. The Mexicans have been doing a lot of work on their

roads in the last five years but AAA hasn't noticed."

Was he planning on going back to Canada to work?

"I've got an electrical engineering degree, but I haven't worked in engineering

for some time. At the moment, I don't have any plans to leave Costa Rica."

"I've got an electrical engineering degree, but I haven't worked in engineering

for some time. At the moment, I don't have any plans to leave Costa Rica."

We pulled into the Hotel Fonda Vela for the Monteverde Music Festival. Eight dollars bought a ticket into a beautiful three-story high wooden room, in front of which ten members of the San Jose symphony played chamber works. Acoustics were excellent and the performance was quite good. By chance, we were seated next to Lucky and Wolf Guindon.