How big is Alaska? If you are in Anchorage and want to catch a ferry to

Juneau or "Outside," you have to drive 900 miles first.

How big is Alaska? If you are in Anchorage and want to catch a ferry to

Juneau or "Outside," you have to drive 900 miles first.

How big is Alaska? If you are in Anchorage and want to catch a ferry to

Juneau or "Outside," you have to drive 900 miles first.

How big is Alaska? If you are in Anchorage and want to catch a ferry to

Juneau or "Outside," you have to drive 900 miles first.

Under mostly blue skies, I said good-bye to Anchorage and drove for

several hours through the awesome Matanuska Valley to Glenallen. The

highway rides the edge of a mountain range and looks across a

glacier-carved riverbed to another range, very much as in Denali

National Park. After 200 miles I rested up in a cafe and then hit the

road around 6 o'clock for Tok. With the massive 20,000' Wrangell

mountains on my right and the end of a broad rainbow in front for nearly

the whole drive, it was a near-mystical driving experience.

Under mostly blue skies, I said good-bye to Anchorage and drove for

several hours through the awesome Matanuska Valley to Glenallen. The

highway rides the edge of a mountain range and looks across a

glacier-carved riverbed to another range, very much as in Denali

National Park. After 200 miles I rested up in a cafe and then hit the

road around 6 o'clock for Tok. With the massive 20,000' Wrangell

mountains on my right and the end of a broad rainbow in front for nearly

the whole drive, it was a near-mystical driving experience.

I pressed on past the "Cheapest Gas for 2000 Miles" sign to the Canadian border with the glorious sunset behind me. Thirty miles into Canada, I pitched my tent at the first likely looking spot and collapsed.

Sunday, July 25

Getting breakfast on this stretch of the AlCan provided as good a lesson in rudeness as 10 years in New York City. All the Canadians who want to be in the service industry but whose personality is maladapted to the task seem to have congregated here. "If you don't like the surly service and the shocking prices, you can just drive 250 miles to Whitehorse."

Well, I did just that and, aside from the usual beautiful mountains and Kluane Lake, saw a big white/gray wolf 25 yards from the road. At 5:00 PM, I pulled into Whitehorse to find the town denuded of all of the people I'd met on my last visit. Every had gone to the Dawson City Music Festival, six hours north of here. This should give you some insight into what day-to-day life in Whitehorse is like; imagine an entertainment event in Philadelphia drawing most of the inhabitants of Boston.

Klondike Highway 2 to Skagway is one of the most scenic two-hour stretches of road anywhere up here. Half the trip follows a series of enormous lakes through which 19th-century prospectors navigated in whatever scraps of boats they'd managed to bring up from San Francisco. The last bit rides the edge of a gorge to crest at 3290' White Pass. This is the route of the White Pass and Yukon narrow-gauge railroad, completed in 1899 to service the gold rush.

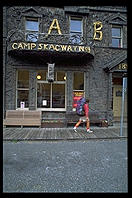

Skagway provides a warm welcome to the traveler returning to the

U.S. and was the first Alaskan town I saw with any character.

Anchorage and Fairbanks were built in a series of booms, and most of

the seaside towns were destroyed by tidal waves during the 1964

earthquake--a 300'-high wave moving 500 miles/hour can do some damage.

Skagway's old wooden buildings were never ravaged by anything other

than time, and many have been restored for tourists, who constitute the

main industry for the town's 700 residents.

At Moe's Frontier Bar, the "oldest operating bar in Skagway," Samantha attracted the interest of William, a German-American farmer from Ohio in the final stages of drunkenness. His intoxication was perhaps unsurprising for someone who has been here for five months and has spent "$4500 drinking, $500 eating, and had a spectacular time all the way." He is doing maintenance work at a hotel here for the summer, but has to "get back and see what my crops are doing. I don't trust people to do my job." He'd like to stay forever.

"I came up here to fulfill a lifelong dream. I was born 100 years out of my time. I enjoy the outdoors so much that I can't live without it. Once you come to Alaska, it is in your blood. You will return."

Sam, a 41-year-old pioneer woman, had just come down here from Anchorage in a motor home with her husband, Ken.

"We came here to see southeast Alaska. The only way to see it is to

live here and take the Marine Highway. You have to be part of it."

"We came here to see southeast Alaska. The only way to see it is to

live here and take the Marine Highway. You have to be part of it."

Ken used to work in Prudhoe four weeks on, four weeks off, and they were very happy together for years. Prudhoe hasn't been paying that well recently, and they laid Ken off in June.

"Now that he's come home it is `like no, that's a whole `nother lifestyle.' I appreciate the fact that I have a man who will take care of me for the rest of my life if I so desire, but right now I can't say that I love Ken. Alaska has given me the courage to make it on my own. This is a paradise for a woman who knows how to take advantage of the situation."

I'd pictured Ken as a loutish fellow with dirty fingernails from working the oil rigs and was quite surprised when a lean soft-spoken Texan approached us. He held a beer but was the most sober-sounding person I'd spoken to in the bar. Although he'd just learned from Sam that she wanted out of the marriage (his second), he encouraged me not to be afraid of marriage.

"I've had several wonderful phases in my life, and I know that somehow the next one will be good also."

Ken's attitude reminded me of Socrates's advice: "By all means marry. If you have a good wife, you will be happy. If you have a bad wife, you will become a philosopher."

Ken and Sam invited me to join them in their spacious 33' motor home for

the night, but I pitched my tent a few paces off instead. I didn't want

to crowd out their pets: a sweet-tempered Doberman bitch, a playful

Husky dog, and an enormously fat gray cat. I had such a good time

slapping my hand against the Husky's hollow chest that I didn't get to

bed until 3.

By 10:30 when I woke, Sam had gone off to her job at the supermarket.

Ken invited me in for a tea and a shower. Even after I'd broken the

shower head support, Ken left me in possession of the $55,000 motor home

while he went to the post office. Ken invited me to Howard and Judy's

trailer, where a bountiful picnic lunch awaited. Judy's mother was

visiting from Kansas and had made raspberry pie with raspberries picked

from local roadsides.

After lunch I poked around downtown Skagway and, not being a souvenir hunter, quickly exhausted most of the diversion available here. I lined up to get on the ferry, but after an hour nothing seemed to be happening. I got out to ask the driver of the van in front of me if I was in the right line. All I could see were delicate feet propped up on the top of the red van's door, then slender legs leading back to a reclining woman with the face of a Spanish aristocrat framed by long dark hair. Lurking in the back were two teenage boys. Judy rolled down her window and told me, in a dulcet Tennessee accent, that the ferry would be late. Judy had a fund of interesting conversation, starting with a story about a friend who had adopted a Czech girl.

"She'd been in a Czech orphanage where conditions were so straitened that a group birthday party was held each month with an inflatable plastic birthday cake. Each child who'd had a birthday that month got a picture of himself."

As we drove onboard, past numerous "stowaways will be prosecuted" signs,

one of the crew offered to maneuver Judy's van for her. She refused to

give him the satisfaction so he directed her with the admonition "stop

trying to drive and just watch me." Sexism rules here in the wild

North. My van is festooned with a bike rack on the rear and the pile of

junk inside limits rear visibility. Nonetheless, the same guy just gave

me instructions, watched my progress, then complimented me on a job well

done.

I started my tour of the ship in the "solarium." As there is typically precious little real sun in this part of Alaska, heat lamps hang over cheap plastic chaise longues. These are highly prized, and a stampede for them had apparently ensued earlier. The winners were mostly two groups from Trek America. Trek America loads 14 people into a van for several weeks and takes them camping through different parts of the U.S. The usual contingent of Germans was supplemented by a lanky Australian girl, a cheerful 26-year-old Dutch printer who'd fallen in love with but been rebuffed by a neurotically thin 23-year-old French-Swiss bleached blonde, and two real live Americans. They were well prepared for the straight four-day trip down to Bellingham, but they weren't the best prepared travelers. At least a dozen people had actually pitched tents on one open deck!

Chilkoot Inlet was so calm that we could hardly feel the boat moving past

the stately mountains. We docked in Haines at around 6:00 PM. Haines is

famous for its annual gathering of bald eagles. Alaska has more of

these birds than the rest of the U.S. combined, and they congregate here

in October through January to feed on the last of the salmon running up

a river that curiously remains unfrozen. About 4000 birds show up

usually, which is less than in olden days but pretty impressive

considering that eagles were once hunted mercilessly by people anxious

to increase the supply of fish. Biologists concluded that the birds

mostly ate "spawned-out" salmon that were about to die anyway and were

of no commercial value (salmon actually start to decay as they swim

upstream and are rather moldy by the time they spawn). Fans of Big

Government might wish to know that the Feds used to pay a $2 bounty for

every pair of talons hacked off of our national symbol; now they give

you a free trip to The Big House if you so much as insult a member of

this endangered species.

Most guidebooks rate Haines a fairly ugly little fishing village, but I'd heard people describe it as their favorite spot in southeast Alaska. I just had to see for myself so I took advantage of our two hours in port to hop a taxi with Judy and the kids to beautiful downtown Haines. Had they not been shrouded in thick clouds, the surrounding peaks running down to the water would have made for a dramatic setting, albeit not very different from the rest of southeast Alaska. However, the town's buildings are solidly in the boomtown mold. Even the fabled harbor isn't much to look at. Virtually all boats in Alaska are newish fiberglass or steel affairs. That quaint wooden fishing boat you might find in New England? The murderous elements here sent it to the bottom a long time ago.

After dinner we cabbed back to the boat, and Judy found that she'd left her tickets in her van. A crewman didn't want to let her board, but she remained impassive and unperturbed. Judy was the first member of her northern Italian/English family to attend college, and she got there through sheer tenacity.

"I was the parent after age 7."

Sure of her correctness and possessed of iron determination, Judy was used to having her way. She'd married at 19 and divorced at 27. The divorce was her idea--no man had ever left her--but it was still incredibly painful.

"It isn't that one mourns the loss of the partner; one is sad for the death of dreams of doing things together," Judy noted.

With two boys to care for, Judy has stuck to practical education and careers. She got a degree in psychiatric social work but now has a hospital administration job. Jason, her 14-year-old, is a professional actor in Memphis theater, while Justin, the 12 year-old, is more devoted to video games. The three of them were so close both physically and emotionally; I wondered what it would be like to marry a woman with kids and know that a big part of her heart would always be reserved for her children.

Sitting with Judy and her family, I plowed through Touching the Void, a shocking tale of two English guys who climbed a 21,000' mountain in the Peruvian Andes. On the way down, Joe fell and broke his heel and leg in a way that twisted his knee into a pretzel. Simon lowered him down 300' at a time and then lowered himself down with frostbitten hands. Halfway through each descent Joe had to unweight the rope so that Simon could move a knot through a piece of climbing equipment. On about the seventh descent, Joe was just hanging in midair. Thus did matters stand for about half an hour. Then Simon's snowseat began to collapse, and both climbers were about to fall to their death. Simon cut the rope and Joe fell into a crevasse. When Simon reached the opening of the crevasse, he could hear no response from Joe and left him for dead.

Simon made it back to base camp laboriously and spent a few days recuperating there. Meanwhile, Joe crawled out of the crevasse, down a glacier, and into camp. He did this with excruciating pain in his leg and no food or water for three days. Simon was about to break camp when he heard Joe's screams for help. Joe eventually got back to civilization and, 10 weeks after the last of six operations, was climbing again in the Himalayas.

Clouds mostly obscured the moon, and darkness blotted out what is supposed to be wonderful scenery. By 10:30 pm people started to sprawl out on the loungers and lost all sense of shame. Jason and Justin couldn't stop laughing at a German fellow whose blanket had slipped off, revealing hairy legs and comical underwear. We drove off the ferry at 1:00 AM, more than two hours late, and drove straight to Mendenhall Lake campground. Judy and Justin slept in their van; Jason and I each pitched a tent in the woods.

You may have had your rope cut in the Peruvian Andes. You may have

taken over Bugs Bunny's job testing artillery shells for duds (by

striking them on the tip with a hammer; the ones that didn't explode

he set aside as duds). You may even have gotten married. But you

don't know the meaning of fear until you've slept next to a

14-year-old with a loaded double-barrel shotgun. Judy abhors guns, but

her brother insisted that she take a shotgun to Alaska for protection

from the bears.

You may have had your rope cut in the Peruvian Andes. You may have

taken over Bugs Bunny's job testing artillery shells for duds (by

striking them on the tip with a hammer; the ones that didn't explode

he set aside as duds). You may even have gotten married. But you

don't know the meaning of fear until you've slept next to a

14-year-old with a loaded double-barrel shotgun. Judy abhors guns, but

her brother insisted that she take a shotgun to Alaska for protection

from the bears.

Tuesday, July 27

After a little bit of hiking around a grayish lake fronting the massive Mendenhall Glacier, I visited the Alaska State Museum in downtown Juneau. I especially enjoyed the exhibit on the Russian period in Alaska, which was from the 1740s until 1867. Russia was worried that the discovery of gold in Alaska would bring in a flood of people and that they'd not be able to hold the colony. They were worried about British encroachment and saw American ownership as the best practical outcome. It was actually the Russians who pushed us to buy the place for $7 million.

Why does every city with a hill call itself "little San Francisco"? I have two arms and two legs, but I don't call myself "dark-haired Robert Redford." Some of Juneau's streets are steep, but not because there are hills; rather, the city is cut into a mountain side like Honolulu. With under 30,000 population, Juneau survives on two industries: state government and milking cruise ship passengers. Alaskans have been talking for 20 years about moving the capital to a small town near Anchorage but are never quite ready to spend the money to do it. Alaska's Inside Passage is one of the world's most popular cruise routes, and Juneau is the only city the passengers see after Seattle or Vancouver. Three enormous ships were in port today, and their passengers thronged five blocks of souvenir shops hawking everything from fudge to Eskimo Ulu knives.

I started my bike tour of Juneau by the cruise ship dock and from

there rode up 250' to the top of one of the city's highest hills.

Some of the views are impressive, but industrial blight and the lack of

a Golden Gate Bridge makes comparison with San Francisco a bit absurd.

Once over a bridge to Douglas Island, a residential suburb, I looked

back at Juneau fronted by the Gastineau Channel. The channel was a

beehive of activity, with float planes roaring past dozens of big

ships. Sunshine broke through a few clouds, continuing the streak of

extraordinarily good weather.

I started my bike tour of Juneau by the cruise ship dock and from

there rode up 250' to the top of one of the city's highest hills.

Some of the views are impressive, but industrial blight and the lack of

a Golden Gate Bridge makes comparison with San Francisco a bit absurd.

Once over a bridge to Douglas Island, a residential suburb, I looked

back at Juneau fronted by the Gastineau Channel. The channel was a

beehive of activity, with float planes roaring past dozens of big

ships. Sunshine broke through a few clouds, continuing the streak of

extraordinarily good weather.

After 13 miles my feet were hurting from my too-tight bike shoes, so I decided to drop into a bike shop. I had a brand-new pair of Shimano bike shoes that fit nicely, but couldn't get them to engage securely in my SPD pedals. Rey and Hans at Mountain Gears figured out the problem: Shimano's shoes recess Shimano's cleats too much to ever fit in Shimano's pedals. With this kind of engineering a Japanese company manages to control 98% of the mountain bike component market. It is kind of heartening that they aren't invincible on the one hand; on the other, if they leave so many loose ends, why can't American companies compete in this area?

After a light dinner, I drove to Salmon Creek power substation to meet eight guys for what was described as an "easy ride with just a little hill at the beginning and a couple of slightly technical parts at the end." The English have nothing to teach Alaskans in the department of understatement. Quite a few tourists here noticed that "just go four blocks down and take a right" might involve 20 miles of driving. Well, the "little hill" turned out to rise 500 feet in about 300 yards. A few people walked most of it, but I was determined not to be seen as an "East Coast wimp" and managed to make it up in the saddle.

After grunting nearly straight up the mountainside, we cruised on a flat gravel road for awhile before turning off onto a singletrack trail. The singletrack began with big trees horizontally across the trail three feet off the ground.

"Slightly technical." Uhh... yeah.

Each time we came to a creekbed the trail would dip down about five feet and then rise up again steeply with boulders, roots, and railroad ties in the way. Many of the guys managed to bunny hop over nearly all of the obstacles, executing maneuvers I'd only ever seen in competition.

It was the stairs that got to me.

The first set of three stairs dropped down four feet; Hans and Rey went down without blinking. The next stairs rose up about four feet to a wooden bridge. Each biker would pull a big wheelie and hit the stairs with both wheels at once, then pedal like crazy to scramble up to the top. Just to the side of the stairs was a rocky 10' slide down to the stream. It wasn't long before Darren fell off the stairs and dumped himself and his $2500 Klein bike down the slope. Several parts of both the bike and Darren's body needed trailside repair.

Nearly everyone was riding $3000 titanium bikes with shock absorbers, but no one laughed at my pathetic clunker. There was a lot of good camaraderie and no macho posturing over who could ride which sections and who couldn't. The forest scenery was well worth all of the effort. Huge ferns and extensive mosses gave the place an enchanted flavor, and it looked like old growth whether it was or not. Mosquitoes weren't a problem, but some kind of biting black fly was pretty irritating when we stopped.

Going down was truly terrifying. We dropped 750' at high speed over rocks and roots that felt much larger now. The thick forest and gathering darkness made it tough to see as well. I'd wondered why all these experienced bikers were riding brand-new machines, but the final toll provided an answer: one derailleur smashed into pieces by a rock, another thrown out of adjustment, sheared-off brake and shift levers, numerous scratches to bike frames and human legs. You're lucky if a bike lasts one season here.

We sailed from Juneau at 2:30 AM. I took a delicious, copious, free shower on board and went upstairs to the solarium deck to sleep. All the "food warmer" bunks under the overhang were taken, but I preferred to sleep in the open anyway. I spread a Thermarest on a chaise longue, stripped, and crawled into a down sleeping bag. The mountains of Juneau receded into the distance, black under a crown of bright sky. The fresh breeze, glass-smooth water, scattered overhead clouds, and stars made for a magical 15 minutes of contemplation before my tired body collapsed into sleep.

A cloudless blue sky spread over forested hillsides in the morning. We hugged the coasts of numerous little islands and passed through so many channels that none of the passengers could say with confidence where we were. The beaches were dotted with the occasional deer or Indian fishing settlement.

I lunched with Gil and Shavit, an Israeli couple fresh out of the army. They were seeing the world for a year before going to university. Gil had fallen in love with what he thinks is the U.S.

"You have it so easy here. You can work just a few months a year and yet live better than 99% of Israelis. The scenery and wildlife here are incredible; there is nothing on this scale anywhere in Europe," Gil said.

I reminded him that coming to Alaska, the least densely populated state in the U.S., from Israel, the most densely populated country in the Mediterranean, wasn't the best way to get perspective on ordinary American life. Had he been to New York City?

"We spent a few weeks there with relatives. It was wonderful. There is so much freedom and open space. It would be a dream to settle here."

At 3:45 pm we sailed past Mt. Edgecumbe, an extinct volcanic cone, and docked in Sitka. This island was once the capital of Russian America and currently is home to about 8500 people. Taking advantage of the rare sunny weather, I hauled my bike out of the minivan and pounded out the seven miles to town. The road hugged the shore and afforded beautiful views out over the water, but the population seemed curiously housed. Half the people live in houses that are quite stylish by Alaskan standards, and the other half live in rusting trailers squatting on the ground. Newish Japanese cars are often parked in front of the trailers so it isn't poverty per se that has reduced people to this, just indifference to their temporary home between fishing trips. I earlier echoed Thoreau in arguing that people put too much time, money, and effort into their shelter, but a cluster of rusting old trailers is pretty ugly. Hey, consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.

From smack in the middle of downtown one can see snow-capped granite peaks, dark green forests, the Gulf of Alaska, a rebuilt Russian Orthodox cathedral, and hundreds of fishing boats. I wheeled into Sitka National Historical Park and learned some of the island's history.

Russians started their settlement of Alaska in the Aleutians and were primarily interested in otter pelts. Otters, the only marine mammal without insulating blubber, have incredibly fine fur. After they'd decimated the Aleutian otter population, the Russians decided to exterminate the fur-bearing critters of southeast Alaska and built a fort here in 1799. Local Tlingit Indians, armed with modern weapons, captured the fort and killed most of the Russians.

Forgiveness in warfare is not a traditional Russian value; they came back in 1804 with a gunboat and beat the Tlingits this time. After their victory, the Russians moved in whole hog, tarting up the town so much that it called itself the "Paris of the Pacific." To this day, Sitka claims to be the cultural center of the southeast, despite the loss of population that ensued when the capital was moved to Juneau in 1900. I missed the June chamber music festival and the July 4th ax-throwing contest, and hence was unable to verify this claim.

Totem poles once used by Indians to decorate houses have been beautifully restored, then incongruously strewn along a wide one-mile trail through the tangled fairy-tale 10,000-year-old cedar forest that was the 1804 battleground. In addition to the massive root systems of overturned trees, one can see the harbor and the Indian River from the peaceful trail.

Downtown Sitka sports two blocks of touristy shops for the cruise ships. I picked up a few chocolates and raced back to the ferry just a few minutes before our 6 o'clock departure. I never did find much evidence of Sitka's Russian flavor, unless you count the filth-spewing ancient pickup trucks that rushed by me on the island's one road.

Sleeping outside again was lovely for awhile, but at 5:00 AM a steady cool rain began to fall. I retreated under the deck and was roused at 6:00 AM by a retired couple. Not only do those over 65 get to ride the ferry for free, they get to spend a full hour rustling around in plastic bags and talking loudly while others are trying to sleep. Where were Karin and Walter now to sing the praises of America's traveling senior citizens?

At 8:00 AM, I drove off the ferry into Petersburg, a fishing village of 3,500. As in every other town in southeast Alaska, my car radio found only two FM stations: a Gospel station and Alaska Public Radio. If you listened to the public radio station carrying NPR news you might think that southeast Alaskans were just like folks anywhere else in the US. But then Morning Edition is interrupted by local news, 99% of which concerns where to find animals to hunt.

Samantha and I ensconced ourselves at La Cafe Agapé.

"Agapé is a Greek word from the New Testament meaning unconditional love, the God kind of love," explained Lavonne, the proprietrix.

You can probably guess which radio station she'd selected.

Lavonne was preparing the annual Christian retreat for her three children and other members of her Faith Christian Fellowship. They'd had good weather in three previous years because "children's prayers are always answered."

How did she square that with the recent flooding of the Midwest?

"Maybe they just weren't praying."

At Petersburg Fisheries, I was greeted cordially by Bruce, manager of

PFI's relations with the fishing fleet. Although PFI owns four

massive factory boats, it buys most of its fish from thousands of

small operators. PFI does whatever it takes to support small-timers

in the ocean. They send a tender to visit fishing grounds and haul

the catch back 80,000 lb. at a time in a refrigerated hold. They

send their float plane out with spare parts to boats. "Petersburg

fishermen have a reputation as some of the best all over Alaska,"

Bruce noted. "You'll find Petersburg boats crabbing the Aleutians and

spread out all over the southeast."

At Petersburg Fisheries, I was greeted cordially by Bruce, manager of

PFI's relations with the fishing fleet. Although PFI owns four

massive factory boats, it buys most of its fish from thousands of

small operators. PFI does whatever it takes to support small-timers

in the ocean. They send a tender to visit fishing grounds and haul

the catch back 80,000 lb. at a time in a refrigerated hold. They

send their float plane out with spare parts to boats. "Petersburg

fishermen have a reputation as some of the best all over Alaska,"

Bruce noted. "You'll find Petersburg boats crabbing the Aleutians and

spread out all over the southeast."

Patrick, a handsome 35ish bachelor with dark hair and mustache,

manages the 600 seasonal workers in the cannery itself. His

competence and confidence were palpable as I observed him talking to

workers and customers (two of whom are Canadians supplying Ontario

fish and chips shops with 5 million pounds of frozen halibut each

year). Patrick walked me around the plant, beginning on the dock. A

salmon starts its journey into the cannery from the seawater-filled

refrigeration hold of a boat. An enormous pump on the dock pumps

water and fish up to the dock while a worker stands hip-deep in

foaming dead-fish-filled water in the hold.

His job is to move the pump intake hose around to gather up all the

fish. Four pleasant college kids on the dock sort the fish into bins.

Some are discards, some are useful only for roe.

Patrick didn't want me photographing the fish disassembly areas so we

headed straight to where glistening orange roe is separated from fish

guts and packed up to be sent to Japan.

After my tour of the working cannery, I have one piece of advice:

Don't take any nice clothes to your job here; even stuff that I left

in the car smelled like fish afterwards.

I went to neighboring Chatham Strait Seafoods to get an idea of what

Patrick hadn't shown me, but my request to take photographs was

politely brushed off due to "insurance problems." Rick, a machinist

who keeps their 90-year-old custom-made equipment up and running, walked

out of the office with me and noted that "they think no one will eat

canned salmon if they see people up to their waists in fish guts. It

is all clean, the FDA lives here, but it isn't necessarily pretty."

Rick gave me a tour of a nonoperating line. Fish come in on a

conveyor and are manually aligned with their gills under a clamp.

They roll down another conveyor with their gills clamped and a knife

chops off their head. A really frightening machine slits open their

bellies and a rotating brush eviscerates the fish before a final

section chops off the tail. Until the early 1900s, this job was done

by Chinese laborers, and the mechanical replacements are called "Iron

Chinks." In fact, I saw one with that appellation cast into its

faceplate.

From conversations with cannery workers, I pieced together a portrait of their lives. They get paid only about $6/hour, but they work 18-22 hours a day and rack up the overtime.

"Four hours of sleep feels normal to me," noted Pam, "and I just sleep in my office in my clothes. All I have to do is hand out equipment. When someone needs something, they just knock and wake me up."

Her friend Pat doesn't worry about falling asleep and injuring herself.

"My job is just inspecting fish. Anyway, the cannery is pretty

safety-conscious. Guys who stuff fish near rotating knives have their

hands secured with steel cables so that they can't get within six

inches of the knife."

Petersburg's gloomy weather made me face the fact that I wasn't ever going to succeed with America OnLine. I decided to switch to CompuServe, an allegedly more reliable competitor of America OnLine's. Hooking up to CompuServe's 20-year-old mainframes involved hours of trial and error and voice calls to their 800 number. Thoroughly frustrated with America's commercial computer networks, I decided to seek solace in religion. I accepted Lavonne's invitation to the "Are You a Slave?" lecture at the Faith Christian Fellowship. A reformed alcoholic was supposed to explain how Jesus saved him from bondage to alcohol.

An older woman welcomed me warmly and pressed my hand in both of hers, asking, "Are you alone?" She seated me in the middle of a square chapel with a suspended ceiling and fluorescent lights over pews comfortably padded and covered with red polyester. The white walls were bare save for a map of the world with Alaska enlarged and three banners ("Christ Lives," "Jesus is Lord," "Because He Lives We Too Shall Live").

I arrived in the middle of singing by three women in front with the congregation joining in, mostly waving their hands in the air and sweating profusely. Having spent much more time at MIT than in synagogues or churches, I assumed that each sermon would build upon the previous sermons much as successive calculus lectures might. I was therefore surprised that Lloyd, the local pastor, said a lot of things that should have been basic to most of his parishioners. Obvious or not, everyone seemed happy to hear it all said again, and Lloyd was rewarded by the congregation. Every 15 seconds they said, "Amen" or "Praise God."

After the collection plate was handed `round, the main event began with an introduction from Cindy Rhorer, the ex-alcoholic's wife.

"We feel so blessed to be here in Alaska. The only time we've been here is flying back from Moscow through Anchorage. We felt blessed to be in America and kissed the ground. It isn't that our country is so great, but that other countries are so bad."

Don't be quick to accuse Cindy of obstructing international understanding. She has visited many poor countries filled with "new Christians who don't know a lot about the Devil." In many of these blighted spots, she has healed the sick. Her prayer cured a man of his color blindness and gave a hip to a woman who was born without one.

Richard Rhorer walked on in a black shirt, flowered silk tie, and gray suit. This 50-year-old makes up for his weak chin with a California, longish, blond hair style and trim body. His home church is in Irvine, California, and he reminded me of nothing so much as an L.A. rental property agent. Rhorer was a captivating dynamic speaker who made good use of wild gestures and bulging eyes.

My previous experience with religious ceremonies was limited to established churches. Two points that struck me here were references to the possibility of backsliding and leaving the faith and constant reminders that this church serves only a select group of enlightened folks. Established churches want everyone to come and listen, in the hopes that maybe someday they'll learn. Rhorer told people time and time again that "if you want to hear about <Jezebel, rituals, etc.>, you're in the wrong place."

Self-improvement via confrontation with the Devil was the main theme of the sermon. Rhorer contrasted the obvious efficacy of Jesus versus secular systems such as EST. Stepping down from the podium to pace back and forth in front of the first pew, he reached out to the crowd with his hands.

"How many of you have had a dream, a vision, a heart, something that you know is a vision from God? [Thirty percent raise their hands.] Don't quit; that is the seed the Devil wants. The Devil is only afraid of the anointed. He fights whenever you start to get good at something worldly, e.g., singing. That is why it is tough to get good at things. God wants you to be successful financially. He has a plan for you laid out in Deuteronomy. But the Devil puts obstacles in your path. If you look the Devil in the face, he won't have anything to say to you. You can be successful."

Rhorer had me fairly well convinced that the Devil was in fact an omnipotent being behind most evil, but his last comment about a sickly little human being able to stare down the Devil let the air out of the Devil for me. Is the Devil stronger than we are or isn't he?

Rhorer ended the evening by exhorting everyone to return for the next four evenings and also buy some of his previous lectures on tape. I chatted with the congregation and Lloyd, the pastor, while people were milling about. Nearly everyone in the room had been cured of some kind of substance-abuse problem by Jesus.

After the revival meeting, I went to Tent City, where enormous tarp palaces cover wooden platforms over the boggy forest. Cannery workers pitch ordinary tents under the tarps and live there for the summer, with hundreds of people sharing two small bathrooms and a coin-op shower with a tiny hot water tank ("a good time to take a shower is 2:00 AM"). America, where everyone lives well...

There was space at a couple "guest platforms" hard by the noisy shelter/kitchen and parking lot. I pitched my tent in a light rain and went into the shelter to find Gil and Shavit with a couple other Israelis from the ferry strumming the guitar and singing American songs. They told me about their evening at the city dump. Twenty black bears came down from the woods to feed and cavort among the garbage.

"You didn't have to fly all the way to Katmai to see bears," they enthused.

As the Malaspina pulled out of Petersburg, I was shocked to see a crewman picking up paper cups, cigarette butts, and other assorted trash, then throwing it all overboard. Thus did we slip away into the gray passage.

Although the weather wasn't the best, I had pleasant reunions with people I'd met everywhere from Skagway to Petersburg. My most interesting new friends on this leg were Tom and Lisa. Tom is a classical reserved German-Minnesotan who might have stepped out of one of Garrison Keiler's Lutheran hamlets. His spare tall physique is in perfect keeping with his modulated speech and quiet competence. Lisa grew up as a nonobservant Jew in Los Angeles and leans more toward sensitivity.

"Do you like yourself?" Lisa asked over pizza.

Tom rolled his eyes and said, "Another one of your unanswerable introspective questions."

"I'm stuck with myself so it doesn't make any difference, and therefore I don't ask the question," I said.

Tom nodded his approval of this response.

Tom studied mechanical engineering as a Navy ROTC student at U. of Minnesota but never fell in love with working as an engineer in industry. "It really isn't much of a career." Lisa quit her job selling radio advertising time, despite her boss's cautioning, "You're committing financial suicide". They left Ventura, California to spend 16 months on the road in their 22' motor home. Although they arranged for their mail to be forwarded, people who called themselves friends very quickly proved themselves unwilling to go to the effort of writing a letter. It really upset Lisa at first.

"I wonder if they ever really were our friends."

They've gradually become more tolerant of people who've been sucked into the yuppie lifestyle and jokingly ask old friends to "add a `write Tom and Lisa' reminder to your Day-Timer."

Tom and Lisa have fallen completely in love with the road.

"We could spend our lives out here and never see it all. We've had to learn to relax and enjoy where we are, and not worry about what we're missing."

RV living proved so seductive that Tom and Lisa eventually bought Rancheros de Santa Fe Camping Park in New Mexico. "The good news is we'll be closed for four and a half months during the winter."

Saturday, July 31 and Sunday, August 1

Ketchikan is the first Alaskan port of call for most cruise ships. I'd seen a lot of cruise ads showing young attractive people dancing the night away, but the average age of the passengers getting off the three ships in port was somewhere between 65 and dead. In fact, a cruise ship radioed ahead for an ambulance on one of my days in the Southeast and then 15 minutes later radioed to ask for a coroner instead. There had been an "unattended death" of an 80-year-old passenger.

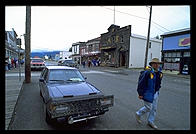

Ketchikan's waterfront is nicely restored and has the full array of

services that you'd expect from Alaska's fourth-largest city (a

population of just 13,000 is enough to secure that title). Tourist

attractions, however, are heavily concentrated in the totem pole

department. Totem poles are fabulous, but you can see them just as

well in the museum in Vancouver as here and with about as much

authentic context.

Ketchikan's waterfront is nicely restored and has the full array of

services that you'd expect from Alaska's fourth-largest city (a

population of just 13,000 is enough to secure that title). Tourist

attractions, however, are heavily concentrated in the totem pole

department. Totem poles are fabulous, but you can see them just as

well in the museum in Vancouver as here and with about as much

authentic context.

I chatted with the usual colorful cast of Alaskans. Esther, a Tlingit

Indian, makes traditional button blankets. Esther was born here 78

years ago, and although a few of her nine children have ventured "down

South," she wouldn't consider living anywhere else. Esther doesn't

cherish romantic notions about Ketchikan, either. "There's crime here

just the same as anywhere else."

I chatted with the usual colorful cast of Alaskans. Esther, a Tlingit

Indian, makes traditional button blankets. Esther was born here 78

years ago, and although a few of her nine children have ventured "down

South," she wouldn't consider living anywhere else. Esther doesn't

cherish romantic notions about Ketchikan, either. "There's crime here

just the same as anywhere else."

As I breakfasted in style at the counter of the Roller Bay Cafe,

Susan, who looked like a young slip of a girl, sat down next to me. I

was shocked to learn that this 24-year-old is the mother of two

children, six and seven. Susan has been going to community college in

Santa Rosa, California, but hopes to transfer to Berkeley, thinking

that her status as a single mother will earn her preference. She has

no regrets about her divorce.

As I breakfasted in style at the counter of the Roller Bay Cafe,

Susan, who looked like a young slip of a girl, sat down next to me. I

was shocked to learn that this 24-year-old is the mother of two

children, six and seven. Susan has been going to community college in

Santa Rosa, California, but hopes to transfer to Berkeley, thinking

that her status as a single mother will earn her preference. She has

no regrets about her divorce.

"We were too young to get married. He's a nice guy, but we weren't meant to be together. I can't imagine getting married again. Why would I want to have to sacrifice myself every day just to get along with another person? I already sacrifice enough for my children."

The highlight of my Ketchikan visit began when I was pushed into a Taquan Air Otter by Doug, the burly pilot. This is just a "single Otter," with one humongous engine in front. For 90 minutes Doug's narration came through my noise-blocking headset. After lifting the floats off the harbor surface, Doug overflew the monstrous local pulp mill and headed inland over Revillagigedo Island. Indian-owned land with massive clear-cuts swept underneath the left side of the plane while national forest land, which is being more gently raped, lay to the right. Doug, a paunchy 45-year-old, explained that the Feds prohibit logs cut in national forests from being exported whole; such logs must be turned into some kind of intermediate or final product. However, in true Third World style, logs from Indian land are merely loaded onto a ship and sent to saw mills in Japan.

One of the first sights Doug noted was a helicopter parked high up a

mountainside. Although there is a fairly extensive network of logging

roads on this island, many logs are lifted out by helicopter to the

nearest road. Once we got into Misty Fjords National Monument, which

encompasses part of Revillagigedo Island and the mainland across a

channel, signs of despoilment evaporated. The landscape here resembles

Yosemite in many ways: bare granite walls of astonishing sheerness,

green forest trying to clothe the naked granite, still lakes reflecting

surrounding peaks. Traditional Yosemite Valley features, e.g., squalid

tent cities, buildings, and traffic jams, are all fortunately missing

from this landscape.

One of the first sights Doug noted was a helicopter parked high up a

mountainside. Although there is a fairly extensive network of logging

roads on this island, many logs are lifted out by helicopter to the

nearest road. Once we got into Misty Fjords National Monument, which

encompasses part of Revillagigedo Island and the mainland across a

channel, signs of despoilment evaporated. The landscape here resembles

Yosemite in many ways: bare granite walls of astonishing sheerness,

green forest trying to clothe the naked granite, still lakes reflecting

surrounding peaks. Traditional Yosemite Valley features, e.g., squalid

tent cities, buildings, and traffic jams, are all fortunately missing

from this landscape.

It is possible to see portions of Misty Fjords by taking an 11-hour cruise, but I think our low-flying plane gave me a much better idea of the terrain. How Doug kept the wings off looming granite walls and spotted mountain goats at the same time was a mystery to me, but we got good looks at clusters of the gentle animals up at 3000'.

After poking our way into a hidden valley, we circled and dropped down

onto a long lake completely cut off from the rest of the world by ridges

1000' above. Doug shut down the engine and let us walk out onto the

float. The airplane is a great way to see Alaska, but the noise that

continues to resonate in one's head for an hour or two afterwards keeps

one from getting a complete feel for a place. It would have been nice

to stay here with a good friend for a day or two.

I thought that there would be nothing like a 40-hour ferry ride for writing letters, polishing up Travels with Samantha, and reading a few thick books. However, this is everyone's last leg on the Marine Highway, and the atmosphere is a bit like a New Year's party. For many, it is nearly the end of their vacation, and for everyone it is a bittersweet farewell to The Last Frontier. Although I managed to finish Barry Lopez's Arctic Dreams, I spent most of my time with old and new friends.

Like my previous rides, this trip was blessed with good weather, unruffled seas, and a smattering of wildlife: 15 killer whales, the occasional beach bum deer, and miscellaneous birds. It all went by so fast and I realized that experiencing the wilderness of southeast Alaska would have required a few weeks in a sea kayak.

One conversation served to underscore how Alaska had changed me. Ever since I'd been skipped from third to fifth grade and lost most of my friends, I'd wanted people to like me. I was telling a story on the boat to a handful of friends and strangers and a Jerry Garcia wanna-be from Seattle interrupted me.

"Aren't you afraid that if you use language like that, people will think you are a sexist?" he demanded.

I responded without thinking, "To tell you the truth, if people don't want to take the time to get to know me, I don't care what they think."