Los Alamos to Boston (September 1994)

by Philip Greenspun

Home : Travel : Footsteps : One Section

Friday, September 23, 1994

I was just getting to really like Los Alamos. I'd met the town

intellectuals and had two or three dinner dates a week and a lunch

date every day if I could tear myself away from my beloved Macintosh

Common Lisp. Weekends with Susie and Stephen in Santa Fe, with its

string of Friday night art gallery openings and super deluxe art

market kept me sane. However, it was getting cold in my tent and I

decided that LANL was a better place to finish a computer science PhD

thesis than to start one. I started driving back towards MIT.

I was just getting to really like Los Alamos. I'd met the town

intellectuals and had two or three dinner dates a week and a lunch

date every day if I could tear myself away from my beloved Macintosh

Common Lisp. Weekends with Susie and Stephen in Santa Fe, with its

string of Friday night art gallery openings and super deluxe art

market kept me sane. However, it was getting cold in my tent and I

decided that LANL was a better place to finish a computer science PhD

thesis than to start one. I started driving back towards MIT.

New Mexico beckoned me back even as I drove out into Colorado. A

cloudless sky overhead and the surreal autumn light made Taos and the

beautiful valley of Arroyo Honda shimmer. I finally understood why

the place attracted so many painters. New Mexicans describe their

state as "Land of Enchantment" or "Land of the Flea and Home of the

Plague" depending upon mood, but I'd concluded for sure that this was

the land of the cracked windshield. I couldn't believe that I'd

survived both the Alaska Highway and a summer in New Mexico with my

windshield intact.

New Mexico beckoned me back even as I drove out into Colorado. A

cloudless sky overhead and the surreal autumn light made Taos and the

beautiful valley of Arroyo Honda shimmer. I finally understood why

the place attracted so many painters. New Mexicans describe their

state as "Land of Enchantment" or "Land of the Flea and Home of the

Plague" depending upon mood, but I'd concluded for sure that this was

the land of the cracked windshield. I couldn't believe that I'd

survived both the Alaska Highway and a summer in New Mexico with my

windshield intact.

Fifteen miles short of the Colorado border, on a smooth highway with

no evidence pebbles, a pickup truck coming the other way kicked up

something that put a dime-sized crack right in front of my eyes.

It was 8pm and almost pitch dark when I got to the campground at Great

Sand Dune National Monument. A ranger narrated a half hour slide show

on Colorado wildflowers, all of which were long dead, for a

miscellaneous collection of Swiss-Germans and Coloradans. Her

presentation was devoid of the usual National Park Service New Age

philosophy except at the end: "next time you look at a wildflower,

feel the wonder." Wind and cold was about to penetrate my Gore-Tex

Thinsulate parka so I was happy to pitch my tent and get into the

sleeping bag. The wind was so strong, though, that it would blow part

of the tent in on my head every now and then. Ear plugs were

essential to keep the howling wind noise out.

It was 8pm and almost pitch dark when I got to the campground at Great

Sand Dune National Monument. A ranger narrated a half hour slide show

on Colorado wildflowers, all of which were long dead, for a

miscellaneous collection of Swiss-Germans and Coloradans. Her

presentation was devoid of the usual National Park Service New Age

philosophy except at the end: "next time you look at a wildflower,

feel the wonder." Wind and cold was about to penetrate my Gore-Tex

Thinsulate parka so I was happy to pitch my tent and get into the

sleeping bag. The wind was so strong, though, that it would blow part

of the tent in on my head every now and then. Ear plugs were

essential to keep the howling wind noise out.

Saturday, September 24, 1994

I managed to push myself out of bed at 6:45 by reminding myself that I

hadn't come all the way here to miss the shadows on the sand dunes.

The scenery was perfect.

A field of Colorado fall color, mostly

yellow and maroon, backed by a 700 foot high sand dune over which

towered the sharp peaks of the Sangre de Cristos. I hiked out onto

the dunes for a bunch of footprint-free shadow-filled shots but felt

no desire to climb all the way to the top through the viscous sand.

I managed to push myself out of bed at 6:45 by reminding myself that I

hadn't come all the way here to miss the shadows on the sand dunes.

The scenery was perfect.

A field of Colorado fall color, mostly

yellow and maroon, backed by a 700 foot high sand dune over which

towered the sharp peaks of the Sangre de Cristos. I hiked out onto

the dunes for a bunch of footprint-free shadow-filled shots but felt

no desire to climb all the way to the top through the viscous sand.

Air conditioning, telephones, satellite TV, and Internet have

ameliorated some of the hardships of life in the real West, but

breakfast at the Oasis cafe just outside the park taught me that it is

still a different world. My waitress had been a passenger in a car

when a rock came through the windshield going 110 mph.

"We're still looking for the truck that kicked up the rock," her

father noted. "She might have been killed if she hadn't had her head

turned sideways."

As it was, she still had some nasty scars and hadn't been able to

start at Arizona State University as planned.

"You can be decapitated by a Kleenex box in the back seat if you stop

short," noted the waitress's young grandmother. We appeared

skeptical. "It's true. If you're going 60 mph, a Kleenex box can

take you head right off."

"If I had to choose between a rock and a Kleenex box, I'd take the

Kleenex," I offered.

"Me too," said the waitress.

I drove through open range in a flat valley north towards US 285, a

scenic route that follows the spine of the Rockies for a thousand

miles or so. I stopped to check out an alligator and fish farm before

pressing on to Salida. Like every Western town, there is the

inevitable strip of WalMart, fast foods, and supermarket, but Salida

has a vital brick downtown as well. I learned that the town was home

to one of America's nicest mountain bike rides, the Monarch Crest.

You take a shuttle bus up to 11,000' for $10, then climb just 1000'

more along the Continental Divide, then ride mostly downhill for the

rest of the 35 mile trip. That's my kind of biking and it broke my

heart not to be able to stay another day in town and do it.

I drove through open range in a flat valley north towards US 285, a

scenic route that follows the spine of the Rockies for a thousand

miles or so. I stopped to check out an alligator and fish farm before

pressing on to Salida. Like every Western town, there is the

inevitable strip of WalMart, fast foods, and supermarket, but Salida

has a vital brick downtown as well. I learned that the town was home

to one of America's nicest mountain bike rides, the Monarch Crest.

You take a shuttle bus up to 11,000' for $10, then climb just 1000'

more along the Continental Divide, then ride mostly downhill for the

rest of the 35 mile trip. That's my kind of biking and it broke my

heart not to be able to stay another day in town and do it.

I ate lunch at the First Street Cafe with Norm, a 5th-generation

German-American who grew up in New Jersey but joined the 10th Mountain

Division and trained at Fort Hale, north of Leadville, Colorado.

I ate lunch at the First Street Cafe with Norm, a 5th-generation

German-American who grew up in New Jersey but joined the 10th Mountain

Division and trained at Fort Hale, north of Leadville, Colorado.

"It was all volunteer and great skiing, but camping in minus 40 degree weather wasn't much fun."

They fought the Germans in the mountains of Italy, 990 of the 15,000 men falling to enemy artillery.

"I was on a ship near the Azores en route to retraining for the

invasion of Japan when we got news about the Hiroshima bomb. I didn't

believe it. There was a guy who'd been a DJ before the war who put

together a daily news show for men on the ship from what he got over

the ship's radio. He was a renowned prankster and none of us who knew

him believed the atomic bomb story. When we found out it was true, we

were walking on air for days."

"I was on a ship near the Azores en route to retraining for the

invasion of Japan when we got news about the Hiroshima bomb. I didn't

believe it. There was a guy who'd been a DJ before the war who put

together a daily news show for men on the ship from what he got over

the ship's radio. He was a renowned prankster and none of us who knew

him believed the atomic bomb story. When we found out it was true, we

were walking on air for days."

Not everyone in Salida is so thrilled with the work of Los Alamos,

however. A downtown storefront is the studio and home of the

artist/agitator Dr. Doom. He campaigns against Republicans, nuclear

arms, and a litany of other right-wing ills by driving around the West

in placard-covered vehicles and dumping drums labeled "nuclear waste"

on roadsides. The election of Bill Clinton has taken a lot of the

wind out of his sails even if nothing substantive has been

accomplished on any liberal front.

After a shower and dip in the Salida hot springs, I spun up through

yellow Aspens, green pines, horse pastures, and bald high passes to the southern

entrance of Rocky Mountain National Park.

Sunday, September 25, 1994

The Shadowcliff youth hostel takes the "hostile" out of hostel with a

glorious view over Shadow Mountain Lake to at least five mountain

ranges. I spent the day hunting great photographs of Aspens,

waterfalls, and the Rockies, but somehow never hit my

photographic stride, perhaps partly due to spirit-lifting but photographically

boring cloudless blue skies.

The Shadowcliff youth hostel takes the "hostile" out of hostel with a

glorious view over Shadow Mountain Lake to at least five mountain

ranges. I spent the day hunting great photographs of Aspens,

waterfalls, and the Rockies, but somehow never hit my

photographic stride, perhaps partly due to spirit-lifting but photographically

boring cloudless blue skies.

Towards the top of the park road, which goes up to 12,183', making it

the "highest continuous paved road in the US," I began to feel short

of breath and get a copper/salt taste in my mouth. A ranger at the

11,750' visitors' center said the metallic taste was a common symptom

of altitude, which reassured me.

Two Malamutes looked perfectly at

home at altitude and their owners turned out to be good souls from

Hewlett-Packard's Greeley scanner division. Two guys came over to

join the fun and when they heard us talking about exchanging JPEGs of

the dogs over Internet asked for the Travels with Samantha URL

because they were students at the Air Force Academy.

Towards the top of the park road, which goes up to 12,183', making it

the "highest continuous paved road in the US," I began to feel short

of breath and get a copper/salt taste in my mouth. A ranger at the

11,750' visitors' center said the metallic taste was a common symptom

of altitude, which reassured me.

Two Malamutes looked perfectly at

home at altitude and their owners turned out to be good souls from

Hewlett-Packard's Greeley scanner division. Two guys came over to

join the fun and when they heard us talking about exchanging JPEGs of

the dogs over Internet asked for the Travels with Samantha URL

because they were students at the Air Force Academy.

Driving in gathering darkness through narrow valleys, I knew that I

was really out of the park when I passed a Vishay sales office.

Hewlett-Packard is taking over Colorado and their Loveland division

apparently buys the fancy Vishay resistors. It was a very lonely and

trying trip on US 34 for an hour before I reached I-76, which punches

diagonially northeast from Denver into Nebraska. I collapsed at 11:30

in an interstate-side motel in Julesberg, Colorado, two miles short of

the border.

Monday, September 26, 1994

Crossing into Nebraska was thrilling out of all proportion to the flat

brown landscape. This was my first new state of the trip and 48th in

my life. Iowa and South Dakota were the only states I'd not visited.

Writing something interesting about Nebraska is a challenge. Doing it

when you cross the state on I-80 in ten hours is impossible. An

average farm started with a fine white farm house in the middle of an

acre of green lawn surrounded by square miles of corn. Iowa is

supposedly the state with the highest percentage of millionaires, but

Nebraska can't be far behind as I didn't notice too many people among

whom this agricultural wealth would have to be divided.

Crossing into Nebraska was thrilling out of all proportion to the flat

brown landscape. This was my first new state of the trip and 48th in

my life. Iowa and South Dakota were the only states I'd not visited.

Writing something interesting about Nebraska is a challenge. Doing it

when you cross the state on I-80 in ten hours is impossible. An

average farm started with a fine white farm house in the middle of an

acre of green lawn surrounded by square miles of corn. Iowa is

supposedly the state with the highest percentage of millionaires, but

Nebraska can't be far behind as I didn't notice too many people among

whom this agricultural wealth would have to be divided.

The

state capitol

in Lincoln is a fine Art Deco monument with a

14-story tower from the top of which Emil, a WalMart stock clerk,

proudly showed me the attractions available to the city's 200,000

residents. Emil was excited to be working in this Walmart which was

three times larger than the one he'd left in western Nebraska. The

governor and local press were coming to see their store's latest

innovation: whenever a mother lost a child in the store, an

announcement would come over the PA system that would cause every

employee to stop work and search for the kid. It sounded sensible,

but then I thought "this is Nebraska, what's going to happen to the

kid anyway?"

The

state capitol

in Lincoln is a fine Art Deco monument with a

14-story tower from the top of which Emil, a WalMart stock clerk,

proudly showed me the attractions available to the city's 200,000

residents. Emil was excited to be working in this Walmart which was

three times larger than the one he'd left in western Nebraska. The

governor and local press were coming to see their store's latest

innovation: whenever a mother lost a child in the store, an

announcement would come over the PA system that would cause every

employee to stop work and search for the kid. It sounded sensible,

but then I thought "this is Nebraska, what's going to happen to the

kid anyway?"

After dinner in the quaint yuppie Old Market section of Omaha, a vast

metropolis of 300,000 an hour east of Lincoln, I debated sticking

around town so that I could stalk pictures for

Heather has Two Mommies in the renowned Omaha Zoo.

Responsibility prevailed and I

charged across the Missouri River for a dark ride through suddenly

hilly Iowa. After the open spaces of New Mexico, dodging the heavy

semi traffic of I-80 at night made me pretty nervous, plus my

headlights seemed to be aimed too high and were irritating other

drivers. It was midnight when I checked into a Days Inn just west of

Iowa City. The desk clerk was a smoking kid from University of Iowa

who was taking a "using Internet" course. He was getting college

credit for reading

Travels with Samantha

on the Web! "Should I

lock the car?" I asked, "I've got a lot of cameras in it."

"This is Iowa. People don't steal things."

Tuesday, September 27

I crossed the Mississippi into Illinois in the "Quad Cities" area,

where chiropractic was invented and is still headquartered. The art

of highway maintenance that is so carefully practiced in Iowa and

Nebraska seems to have fallen into disrepute in Illinois. As the

moonscape of I-80 pounded my bones, I recalled an engineer from

Caterpillar who described his summer working for the Illinois

Department of Transportation.

"They worshipped the twin gods of Waste and Incompetence."

Anxious to get to the

Art Institute before closing time, I passed up

the Ronald Reagan Birthplace, 32 miles off the interstate. I needn't

have hurried. Tuesday is not only "free day" (though the others are

"pay what you can" like the Metropolitan) but "open until 8" day. I

wore out my feet and learned that the museum has a lot of good

pictures but no Vermeers.

Despite my September interlude in Boston, I was overwhelmed by the big

city feel of Chicago after a summer in New Mexico. The scale of the

buildings, lakeshore park, lake, and traffic awed me. Every face

looked as if it betrayed an interesting story. It was

overstimulating, but not quite as nerve-wracking as navigating rush

hour Chicago traffic moving bumper to bumper at 65 mph in a minivan

with no rear visibility due to overpacking.

Despite my September interlude in Boston, I was overwhelmed by the big

city feel of Chicago after a summer in New Mexico. The scale of the

buildings, lakeshore park, lake, and traffic awed me. Every face

looked as if it betrayed an interesting story. It was

overstimulating, but not quite as nerve-wracking as navigating rush

hour Chicago traffic moving bumper to bumper at 65 mph in a minivan

with no rear visibility due to overpacking.

The mills of Gary, Indiana ringing the lakeshore just southeast of

Chicago looked truly Satanic. I wanted to stop for a picture but

couldn't figure out how so I pressed two hundred miles northeast on

I-94 into Ann Arbor, Michigan. For the first hour of my trip, I was

educated by Studs Terkel interviewing Roger G. Kennedy, the director

of the National Parks Service, and author of Hidden Cities, the

Discovery and Loss of Ancient North American Civilization. My

American history textbooks implied that, although the Aztecs and Incas

may have had impressive cultures, that the North American Indians had

never been more than nomads thinking about their next deer supper.

The truth is apparently that the Ohio river valley in the fourth

century A.D. was dotted with cities containing impressive earthworks

and hundreds of thousands of people. This was well-known to George

Washington and his contemporaries who evinced a genuine scientific

interest in these cities if not a respect for the descendants of the

city builders. When white Americans were engaged in a systematic

program of displacing the Indians, they didn't want to think of them

as having been capable of advanced civilization and hence the

knowledge was lost to laymen if not to historians. [Jeff and Lori

assured me later that if I watched public TV instead of the Simpsons,

I'd have learned about this long ago; Anne Marie assured me that if I

grew up near some of the big sites, such as Cahokia, Illinois, just

across the river from St. Louis, I'd also have known.]

Wednesday, September 28 (my 31st birthday)

Phil Donahue flung cheap shots at famous defense lawyers on the motel

breakfast room TV while I munched donuts. Neither Donahue nor his

audience approached the wit of one lawyer: "What's the difference

between a spermatozoa and a lawyer? The spermatozoa has a 1 in 6

million chance of becoming a human being."

University of Michigan has some nice Gothic architecture in addition

to the usual state university Bauhaus horrors. I sat for a moment in

the supremely comfortable and soul-inspiring student union reading the

daily paper. One photo that caught my MIT-trained eye was of the

school's new Star Trek club; it was of four attractive women.

After my

year of litigation with Ford Motor Company, the city they'd

built in Dearborn drew me like a magnet. I skipped Henry Ford's

52-room limestone mansion and the various corporate campuses because I

wanted to concentrate on the Henry Ford

Museum

and Greenfield Village,

whose charms allegedly couldn't be fully explored in less than two days.

After my

year of litigation with Ford Motor Company, the city they'd

built in Dearborn drew me like a magnet. I skipped Henry Ford's

52-room limestone mansion and the various corporate campuses because I

wanted to concentrate on the Henry Ford

Museum

and Greenfield Village,

whose charms allegedly couldn't be fully explored in less than two days.

Henry Ford, who fought a libel suit over whether he said "History is

bunk," built a 12-acre replica of Philadelphia's Independence Hall to

house his treasured documents of American invention. The museum

opened in 1929 and resembles an airplane hanger inside.

Don't look for Smithsonian-style explanations of technology; the

museum's credo is "We gots the

stuff and here it is." Edison's last

breath is in a test tube next to Abe Lincoln's death chair, not far

from the death car of John F. Kennedy, not far from an old McDonald's

sign, across the corridor from a silver collection, adjacent to a

bunch of vacuum cleaners, which are a stone's throw from a bunch of

old wooden farm machinery. Old people say that this is how the

Smithsonian was when everything was housed in the "castle" on the mall

and that it was better then. For them the Henry Ford Museum

represents the last authentic museum experience available in America.

Don't look for Smithsonian-style explanations of technology; the

museum's credo is "We gots the

stuff and here it is." Edison's last

breath is in a test tube next to Abe Lincoln's death chair, not far

from the death car of John F. Kennedy, not far from an old McDonald's

sign, across the corridor from a silver collection, adjacent to a

bunch of vacuum cleaners, which are a stone's throw from a bunch of

old wooden farm machinery. Old people say that this is how the

Smithsonian was when everything was housed in the "castle" on the mall

and that it was better then. For them the Henry Ford Museum

represents the last authentic museum experience available in America.

Irene, a museum staffer, two retired ladies from Oklahoma, and I

paused for a conversation. Surrounded as we were by the greatest

American inventions of the past century, we naturally discussed....

O.J. Simpson.

Irene, a museum staffer, two retired ladies from Oklahoma, and I

paused for a conversation. Surrounded as we were by the greatest

American inventions of the past century, we naturally discussed....

O.J. Simpson.

"Do you think he's guilty?" Irene asked.

"I've been living in a tent all summer with no TV. I'm not educated enough to say," I responded.

The two Oklahoma ladies remarked that it was amazing how many people

thought that he wasn't guilty or that, if he was, he shouldn't go to

jail. They'd never met any of these people, but they'd heard reports

that they existed.

Irene nodded her head but I decided to stir up the pot with a slightly

stretched argument from David Hume.

"Why do you think that everyone shares the belief that justice is

good? For example, if we had a society of superabundance,

property-based laws and courts would serve no purpose. Would there be

any point in prosecuting someone for stealing your car when you could

just as easily walk down to the corner and get another one for free?"

My listeners looked slightly puzzled but I pressed on.

"What if we had a society with resources so limited that you couldn't

get enough to feed your family no matter how hard you worked unless

you stole. People in that society wouldn't think property laws and

courts were useful either. It is only in a middle-class society where

folks believe that reasonably hard work will yield a reasonable

standard of living that justice is considered good. If the TV

networks find a black guy in the ghetto who believes, whether or not

it is true, that there is no honest way for him to get ahead in this

world, there is no reason to suppose that he'd buy into our

middle-class concept of justice. Admittedly O.J.'s crime was a crime

of passion, not of property, but once you get the ideas that courts

and laws aren't serving your community, you probably don't think they

are useful for anything."

Greenfield Village

is a 120-acre confection of Americana, albeit an

extremely inventive and litigious Americana. Henry Ford liked certain

buildings all around the country, especially the homes of inventors

and self-made men of industry. He wasn't content to take snapshots;

he physically dragged the buildings here. Thomas Edison's complete

Menlo Park laboratory is here. The chemical-stained bleary-eyed

workers are gone, but old women relate with pride how he got 1093

patents.

Greenfield Village

is a 120-acre confection of Americana, albeit an

extremely inventive and litigious Americana. Henry Ford liked certain

buildings all around the country, especially the homes of inventors

and self-made men of industry. He wasn't content to take snapshots;

he physically dragged the buildings here. Thomas Edison's complete

Menlo Park laboratory is here. The chemical-stained bleary-eyed

workers are gone, but old women relate with pride how he got 1093

patents.

"If any of the workers got sick, Edison would mix up a cocktail of

chemicals at that bench over there and make them well. They were all

working so hard that they couldn't afford to have anyone sick, you

see."

"If any of the workers got sick, Edison would mix up a cocktail of

chemicals at that bench over there and make them well. They were all

working so hard that they couldn't afford to have anyone sick, you

see."

Edison was Ford's hero, you see, and the whole place was dedicated to

Edison in person when it opened in 1929 (Edison was 82 at the time).

The Wright Brothers weren't far behind and get two spots: one for the

bike shop/workshop and one for their home. Ford was no racist and

Booker T. Washington's house is here to prove it. Nor did his

reputation for Jew-hatred seem warranted standing in front of Mrs. D.

Cohen's perfectly preserved millinery shop.

Edison was Ford's hero, you see, and the whole place was dedicated to

Edison in person when it opened in 1929 (Edison was 82 at the time).

The Wright Brothers weren't far behind and get two spots: one for the

bike shop/workshop and one for their home. Ford was no racist and

Booker T. Washington's house is here to prove it. Nor did his

reputation for Jew-hatred seem warranted standing in front of Mrs. D.

Cohen's perfectly preserved millinery shop.

A whimsical mood prevails in Greenfield Village. A lovely Stephen

Foster memorial fronts the circular pond with working steamboat.

Model T Fords cruise the streets, a steam train circles the complex,

and children ride a wooden carousel. Nothing American would be

complete without various ripped-off parts of Europe, of course, and

Henry Ford wasn't content to replicate a la Busch Gardens. Parts of

the Cotswolds and Switzerland were excised and rest here.

A whimsical mood prevails in Greenfield Village. A lovely Stephen

Foster memorial fronts the circular pond with working steamboat.

Model T Fords cruise the streets, a steam train circles the complex,

and children ride a wooden carousel. Nothing American would be

complete without various ripped-off parts of Europe, of course, and

Henry Ford wasn't content to replicate a la Busch Gardens. Parts of

the Cotswolds and Switzerland were excised and rest here.

Although the $20 combined ticket price isn't very different from

Disneyland's, the corporate stage management and heavy-handed spin

control is absent. The bookshop contains a full selection of

biographies of Ford and none of them gloss over Ford's worldwide

publication of anti-Jewish propaganda from 1921 through 1927, when he

retracted his views, and continuing much later in Germany and many

other foreign countries. The continued popularity and availability of

Ford's work in the 1930's in Germany, Ford's acceptance in 1938 of

Germany's highest honor from Adolph Hitler, and Ford's refusal to

reaffirm his 1927 retraction clouded his reputation further. However,

at the end of the war, Ford began to see and state that he'd been

mistaken about the International Jew and noted that he should figure

out how Hitler and Germany had managed to cause so much trouble. Ford

only had two more years to live so it languished on his "to do" list.

I didn't feel inclined to judge Ford harshly. On the witness stand in

the "history is bunk" trial, he proved embarrassingly ignorant of

history. He seems to have been nice to all the Jews he knew

personally and appears to have refused to finance Hitler despite

rumors to the contrary. It is a tragedy of capitalism that the

ill-informed opinions of the rich assume titantic and profound

proportions in the public mind. We automatically assume that poor

people must be stupid--otherwise why wouldn't we just give them money

instead of social workers, Medicaid, food stamps, etc.--and that rich

people must have done something wonderfully innovative and clever to

get that way.

As the museum closed at 5 pm, I headed through Detroit's mellow rush

hour towards Canada. A gas station attendant warned me to "watch out

for those Canadian drivers." I took his advice seriously, reasoning

that anyone who chose to live in the traditional Murder Capital of the

US was probably not easily alarmed.

My first stop in Canada was the sister city of Windsor, Ontario, where

I photographed the Detroit skyline from the riverfront and chatted

with Leonard, who was fishing, and Candis, his 8th-grader friend. The

metric system doesn't seem to be taking root in Ontario because Candis

said she was more comfortable thinking in pounds than kilograms.

Lower Ontario seems like a flatter version of Iowa: cornfields and

smooth highway. Without federal subsidies, however, the farmhouses

were functional rather than palatial and never surrounded by huge

expanses of lawn. Every acre was put to some use and millionaires

appeared to be thin on the ground.

Lower Ontario seems like a flatter version of Iowa: cornfields and

smooth highway. Without federal subsidies, however, the farmhouses

were functional rather than palatial and never surrounded by huge

expanses of lawn. Every acre was put to some use and millionaires

appeared to be thin on the ground.

Stoked with Poulet McCroquettes from McDonald's, I made it all the way

to Niagara Falls by 11 pm. I remembered being awed by the Falls when

I was 10 on the Great Family Trip to Upstate New York (complete with

sister screaming in the back seat). I had never seen anything on that

scale before. After traveling in the West, Alaska, and New Zealand,

however, the Falls don't seem unbelievable outsized anymore even if

the sheer amount of water staggers the New Mexican mind.

Stoked with Poulet McCroquettes from McDonald's, I made it all the way

to Niagara Falls by 11 pm. I remembered being awed by the Falls when

I was 10 on the Great Family Trip to Upstate New York (complete with

sister screaming in the back seat). I had never seen anything on that

scale before. After traveling in the West, Alaska, and New Zealand,

however, the Falls don't seem unbelievable outsized anymore even if

the sheer amount of water staggers the New Mexican mind.

They'd turned off the lights on the Falls at 11 pm so I shuddered in

the darkness at the lip of the more graceful Canadian Horseshoe Falls

before returning to the solid neon of the tourist streets. The

Canadian side is famously less tacky than the American side, so seeing

wax museums every few meters, a Ripley's Believe it or Not museum, a

Guinness Book of World Records museum, every kind of carnival game and

booth, I shuddered to think what the American side would be like.

They'd turned off the lights on the Falls at 11 pm so I shuddered in

the darkness at the lip of the more graceful Canadian Horseshoe Falls

before returning to the solid neon of the tourist streets. The

Canadian side is famously less tacky than the American side, so seeing

wax museums every few meters, a Ripley's Believe it or Not museum, a

Guinness Book of World Records museum, every kind of carnival game and

booth, I shuddered to think what the American side would be like.

Thursday, September 29, 1994

Thursday, September 29, 1994

Tivoli Miniature World

was my favorite tourist attraction in Niagara Falls. Where else can

you get the Taj Mahal, Arc de Triomphe, and Eiffel Tower all in one

picture with the 600'-high Skylon Tower in the background. Models of

medieval cities and cathedrals are exquisitely detailed and precise.

I even saw Mt. Rushmore, which I'd scratched with regret from my

touring program despite the fact that it would have made a perfect 50

states.

Tivoli Miniature World

was my favorite tourist attraction in Niagara Falls. Where else can

you get the Taj Mahal, Arc de Triomphe, and Eiffel Tower all in one

picture with the 600'-high Skylon Tower in the background. Models of

medieval cities and cathedrals are exquisitely detailed and precise.

I even saw Mt. Rushmore, which I'd scratched with regret from my

touring program despite the fact that it would have made a perfect 50

states.

Determined to make the Falls look as small as Tivoli Miniature World,

I hopped into one of Niagara Helicopters's Bell Jet Rangers for a

bird's eye view of the city, gorge, power project, and Falls. This

was living.

I drove back into the US and straight along the shore of Lake Ontario

past tidy corn, apple, pear, and berry farms. It was painful to go

through Rochester without stopping at any of the Eastman-funded

monuments to photography, but I was anxious to get to Oswego, a couple

of hours east.

Oswego, New York is a dream town for any public relations person

looking for a challenge. The town contains three nuclear power plants

and a concentration camp for Jews.

Friday, September 30, 1994

Fort Ontario's earthen walls sit on high ground above the mouth of the

Oswego River and Lake Ontario. It is a New York State Historic Site

that is being restored to its 1868 appearance. I barged in on Patrick

Wilder and Richard Lacrosse, Jr., the two on-site historians, and

asked about the fort's World War II history.

Fort Ontario's earthen walls sit on high ground above the mouth of the

Oswego River and Lake Ontario. It is a New York State Historic Site

that is being restored to its 1868 appearance. I barged in on Patrick

Wilder and Richard Lacrosse, Jr., the two on-site historians, and

asked about the fort's World War II history.

"We can tell you about that," Patrick said, "but the fort's most

interesting history was during the Revolutionary War and the War of

1812. Fort Ontario was the embarkation point for the world's first

boat people. Did you ever wonder where the English speakers of Canada

came from? `British North America', as it was then called, was just

French settlers and Indians until the Revolutionary War. During the

war, loyalists from all over the 13 colonies came to Fort Ontario,

which was held by the British, and embarked across the Lake to British

North America.

Fort Ontario isn't too far from the Proclamation Line, which was one

of the causes of both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. The

British gave the Indians jurisdiction to the west of the line and the

white settlers jurisdiction to the east. A fellow like George

Washington who'd already claimed 500,000 acres in Ohio couldn't be

expected to be very happy with this arrangement. People forget that

there were revolts not just in the 13 colonies but in the Caribbean as

well and that the goals of the Revolutionary War included establishing

a country that was much larger, including Canada, Bermuda, and the

Bahamas. The settlement of 1783 that ended the war was brokered by

the French.

They told the Americans that the most they could hope to get was the

13 colonies and that promising to honor the Proclamation Line and

compensate the loyalists for their homes wasn't so bad, that they

could possibly gain some of the other goals in the future. So the

Americans signed.

They told the Americans that the most they could hope to get was the

13 colonies and that promising to honor the Proclamation Line and

compensate the loyalists for their homes wasn't so bad, that they

could possibly gain some of the other goals in the future. So the

Americans signed.

Between the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, the population of

the U.S. went from three million to over seven million. That wasn't

from immigration and it was mostly in the northeast. What happened is

that men in the northeast had four or five wives and twenty children.

They'd go through wives the way you'd go through oxen. When one got

worn out and died in childbirth, they'd get another. The oldest son

would get the farm and the rest of the kids would move out to the Ohio

river valley and clear some of the forest the Indians were intent on

preserving. When the Indians would kill one of these guys, his

relatives back in Massachusetts would complain to their Congressmen

and they would pressure the president to send in troops. This caused

the Indians and the British to complain that the US wasn't honoring

the 1783 agreement or the 1796 agreement, which finally ended British

control of forts such as Fort Ontario. In return, the Americans

reiterated their promise to honor the Proclamation Line, which they

didn't, and compensate the loyalists, which they didn't.

Meanwhile, the British were at war with Napoleon. When the Royal Navy

needed a merchant vessel, they'd grab one from the English merchant

marine and pay the owner a fixed sum. The owners didn't like that so

they would reflag their vessels in the US and claim that the ship

could no longer be appropriated because it was American. And what do

you think would happen if a Royal Navy ship pulled into a port next to

an American merchant ship? The sailors on the British ship were

poorly paid, poorly fed, got shot at, and often received the cat o'

nine tails. They'd see the well-fed, well-paid, happy American

sailors on the neighboring ship. There would be a couple of splashes

in the middle of the night and the American ship would have a couple

of new crewmembers.

Meanwhile, the British were at war with Napoleon. When the Royal Navy

needed a merchant vessel, they'd grab one from the English merchant

marine and pay the owner a fixed sum. The owners didn't like that so

they would reflag their vessels in the US and claim that the ship

could no longer be appropriated because it was American. And what do

you think would happen if a Royal Navy ship pulled into a port next to

an American merchant ship? The sailors on the British ship were

poorly paid, poorly fed, got shot at, and often received the cat o'

nine tails. They'd see the well-fed, well-paid, happy American

sailors on the neighboring ship. There would be a couple of splashes

in the middle of the night and the American ship would have a couple

of new crewmembers.

The British didn't like to see their merchant fleet or their navy

shrink so they took to stopping ships on the high seas and looking

around to see if the men or ship had previously been British. If so,

they'd seize the ship and the men and sometimes even hang a few navy

deserters. One time, they even boarded an American warship and took

off a few deserters and when word got to the newspapers, Americans

everywhere were humiliated and outraged.

The war started, though, when the French encouraged the Americans to

take Canada and renounce their agreement regarding the Proclamation

Line. The US expected it to be easy because they figured the French

up there would welcome liberation from English rule.

Well, we lost. It was our first Vietnam.

The French in British North America didn't want to be part of the U.S.

The British let them keep their law, elect their local politicians,

and practice Catholicism. Many of the New England states had

established Protestant churches at the time."

"Oh yes," I recalled, "I think Massachusetts had a state church until 1820."

"That's right, plus they ran into 10,000 British troops. You won't

read about the attempt to take Canada in history books, though,

because we lost those battles. One of the nice things about not being

occupied after a defeat is that you get to write your own history of

the war.... Of course, the Germans and Japanese were occupied and

they've been doing it anyway... Well, if you look at an American

history textbook, what you'll mostly read about is a naval battle in

New Orleans. It was irrelevant to the main currents of the war and we

mostly won because of luck and the fortunes of war, but we won so you

get two pages on it. Nobody mentions that none of the war's

objectives were achieved and that we actually lost some territory.

Anyway, these are the kind of stories that the loyalists who fled to

Canada have been passing down through the generations up there and you

don't have to push a conversation very far over there before you dig

up a different look at the American Revolution."

Most of what I'd thought about the fort's role in World War II turned

out to be wrong as well. A little background may be helpful first.

Although numerous European governments on both sides of the conflict

appealed to the U.S. to shelter some Jews from the Holocaust, FDR was

adamant about not letting a single Jew become an American citizen

throughout the war and he was also adamantly opposed to temporarily

sheltering any refugees. However, by 1944 pressure from countries

such as England had become so intense that FDR felt he had to make at

least a token gesture. Consequently, it was decided to accept one

boatload of refugees.

I'd thought that these 982 people, most of them Jews, were saved from

the Holocaust. However, I learned from Patrick that they'd already

escaped the death camps and were residing in liberated Italy. Thus,

the U.S. was really doing the Italians a favor by taking 982 mouths to

feed off their hands.

Roosevelt wanted to make sure that these folks never became permanent

U.S. residents and imprisoned them in Fort Ontario behind barbed wire.

I thought that he'd succeeded and that they were eventually deported.

However, I learned that the imprisonment wasn't comprehensive during

the war, for school-age children were let out during the day to attend

Oswego Public Schools, and I also learned that FDR's plan was

thwarted.

Congress was also opposed to letting the refugees stay, but Harry

Truman felt sorry for them. In 1946, when Congress was in recess,

Truman unilaterallly ordered all 982 across the border into Canada for

a day and then readmitted to the U.S. by special presidential order;

899 ultimately settled permanently in the U.S. and 50 or 60 returned

recently for the 50th anniversary of the Fort Ontario camp.

Several excellent books have been written on the subject:

Haven:

The Unkown Story of 1000 WWII Refugees by Dr. Ruth Gruber, the

former liaison between the refugees and the government, Token

Refuge, by Sharon Lowenstein, and

Don't Fence Me In, by

Joseph Smart, the former commander of the camp.

I walked around the fort with my camera, but was disappointed to find

that none of the buildings from the refugee camp remain. They were

torn down by the city and state after the federal government turned

the land over to them in 1946. The fort itself is being restored to

its 1868 appearance and the whole park is going to concentrate on this

particularly uneventful period of the fort's history. Exhibits and

information that don't relate to this period will be torn down.

I walked around the fort with my camera, but was disappointed to find

that none of the buildings from the refugee camp remain. They were

torn down by the city and state after the federal government turned

the land over to them in 1946. The fort itself is being restored to

its 1868 appearance and the whole park is going to concentrate on this

particularly uneventful period of the fort's history. Exhibits and

information that don't relate to this period will be torn down.

Today's museum has a very informative well-designed

artistically-presented series of exhibits on the fort's history from

1726 through WWII. All the exhibits are professional with a unified

graphic design, except for the one wall given over to the refugee camp

days. This looks like an afterthought and basically consists of a

bunch of photographs tacked to the wall.

One of the saddest wall hangings is an engraving showing the town of

Oswego in 1852. It looks beautiful and bustling with tall ships at

every dock and graceful buildings at the mouth of the Oswego River.

Today, there are ugly docks and oil storage tanks where the tall ships

once berthed.

Before leaving town, I headed out to the nuclear electricity plant

complex. The first two reactors are cooled with lake water and look

like generic factories. The third and last was built with a

characteristic cooling tower because people were concerned about heat

build-up in the bay.

Before leaving town, I headed out to the nuclear electricity plant

complex. The first two reactors are cooled with lake water and look

like generic factories. The third and last was built with a

characteristic cooling tower because people were concerned about heat

build-up in the bay.

A nice Energy Center explains the wonders of the reactors, how safe

nuclear energy is, and how one eighth of New York State's power is

generated here. Three Mile Island isn't mentioned in the

exhibits.

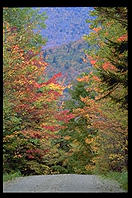

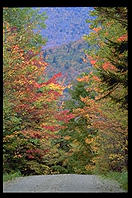

I left Oswego at 3 pm and threaded my way around the east shore of

Lake Ontario and then east into the Adirondacks to Saranac Lake. The

Adirondacks that you can see from the road have a much more settled

look than the White Mountains. There are large areas of

near-wilderness, but one has to get far off the main roads to see

them. Still the foliage was marvelous.

I left Oswego at 3 pm and threaded my way around the east shore of

Lake Ontario and then east into the Adirondacks to Saranac Lake. The

Adirondacks that you can see from the road have a much more settled

look than the White Mountains. There are large areas of

near-wilderness, but one has to get far off the main roads to see

them. Still the foliage was marvelous.

Saturday, October 1

Driving back to Boston through the Adirondacks and southern Vermont in

foliage season may not be heaven, but as a homecoming technique it

sure beats driving up the Jersey Turnpike in the rain after having all

of one's posessions stolen in Filthadelphia (see

Travels with

Samantha, Chapter XVII).

Driving back to Boston through the Adirondacks and southern Vermont in

foliage season may not be heaven, but as a homecoming technique it

sure beats driving up the Jersey Turnpike in the rain after having all

of one's posessions stolen in Filthadelphia (see

Travels with

Samantha, Chapter XVII).

Foliage Pictures

Foliage Pictures

The Adirondacks began to grow on me on Route 73 southeast of Lake

Placid. This was the highest and wildest part of the part so far,

under a blue sky with wispy clouds. At Ft. Ticonderoga, I took a

ferry across Lake Champlain then continued on 73 to 100, the spine of

the Green Mountains. After photographing Moss Glen Falls and Texas

Falls, I stopped for an excellent lunch at the Rochester Cafe in

Rochester. Despite some very interesting conversations with

Vermonters who'd given up the city because they didn't like the pace

and the imposed value system in which things not done to earn a buck

are considered a waste, I regretted stopping. My leisurely lunch

caused me to arrive in Quechee 15 minutes after the last launch of the

day in the Quechee Balloon Festival, which I had completely forgotten

about.

I wish I could say that something really interesting happened in the

last moments of the trip but I-89 and I-93 down to Boston in the dark

are not the places for epiphanies.

The End.

Shameless Advertising

If you've read this far, you might enjoy my other Web books:

Up to the Footsteps cover page.

Up to the Footsteps cover page.

Related Links

philg@mit.edu

Add a comment | Add a link

I was just getting to really like Los Alamos. I'd met the town

intellectuals and had two or three dinner dates a week and a lunch

date every day if I could tear myself away from my beloved Macintosh

Common Lisp. Weekends with Susie and Stephen in Santa Fe, with its

string of Friday night art gallery openings and super deluxe art

market kept me sane. However, it was getting cold in my tent and I

decided that LANL was a better place to finish a computer science PhD

thesis than to start one. I started driving back towards MIT.

I was just getting to really like Los Alamos. I'd met the town

intellectuals and had two or three dinner dates a week and a lunch

date every day if I could tear myself away from my beloved Macintosh

Common Lisp. Weekends with Susie and Stephen in Santa Fe, with its

string of Friday night art gallery openings and super deluxe art

market kept me sane. However, it was getting cold in my tent and I

decided that LANL was a better place to finish a computer science PhD

thesis than to start one. I started driving back towards MIT.

Stoked with Poulet McCroquettes from McDonald's, I made it all the way

to Niagara Falls by 11 pm. I remembered being awed by the Falls when

I was 10 on the Great Family Trip to Upstate New York (complete with

sister screaming in the back seat). I had never seen anything on that

scale before. After traveling in the West, Alaska, and New Zealand,

however, the Falls don't seem unbelievable outsized anymore even if

the sheer amount of water staggers the New Mexican mind.

Stoked with Poulet McCroquettes from McDonald's, I made it all the way

to Niagara Falls by 11 pm. I remembered being awed by the Falls when

I was 10 on the Great Family Trip to Upstate New York (complete with

sister screaming in the back seat). I had never seen anything on that

scale before. After traveling in the West, Alaska, and New Zealand,

however, the Falls don't seem unbelievable outsized anymore even if

the sheer amount of water staggers the New Mexican mind.